The mayor and some of the city council wanted to ban ice cream sales in downtown Carmel, because the sidewalks were getting sticky.

Clint Eastwood liked eating ice cream, so he ran for mayor. At least that’s the reason he gave.

Clint tried to keep his campaign a local one with local issues. He would only talk to local press, and The San Francisco Examiner was considered local press, and only about the campaign. He didn’t speak to national press, and definitely not to the tabloid press.

I couldn't help thinking that even though we had an appointment with him, I wasn’t going to get to see much of him, except from far away.

Having an assignment that requires you to spend the night in Carmel is always a treat. There’s no place to stay down there that isn’t very posh and expensive, and we had an expense account.

Arriving at our more than nice hotel, there was a message from Eastwood’s campaign headquarters. Clint wanted to meet us at 10am at his restaurant, the Hog’s Breath Inn, instead of at his campaign headquarters. This was not good news, the place was dark inside, and if Clint wanted to stay inside for the interview shooting him was going to be tricky, even if I could get him out on the patio, the light there was patchy at best.

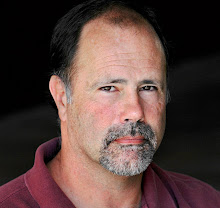

We arrived at the Hog’s Breath at the appointed time, the restaurant was completely empty. Then out from behind the bar came Clint himself. He’s tall, easily 6’4”, and has a slow, Henry Fonda-type walk. His pants are pulled up a little higher than most people, in an almost little old man way, but even though he is older, he’s no little old man.

He greeted us cordially and gently, in a very soft-spoken way. He almost had the demeanor of a funeral director. He looks you directly in the eyes, and you can feel his gaze in the back of your skull. When he speaks he looks away, choosing his words purposefully.

He had some work to do at the restaurant, which is why we were meeting there, but he was almost done. He asked if he could get us something to drink. I said, “No thanks”, in a deeper than normal voice, while trying to stand as tall as I could. Even though I’m about 6'2", I felt like a dwarf, John, my reporter was no more than 5’8”; he didn’t stand a chance.

I noticed another photographer out in front of the restaurant. There was something a little different about his equipment and the way he was dressed. He had a european look about him; a cultured five o’clock shadow, a black photo vest, and a flash on his camera in the daytime. He had to be paparazzi.

Clint came back out from behind the bar. Maybe I could talk him into going back to the campaign headquarters for the photo, now that his work was done. I would explain that the light was better there, and I could get a campaign sign in the background, and maybe some local voters. I had worked out exactly what I was going to say.

As he walked up to me, I opened my mouth to speak, but he spoke first, “Come on”, and walked out the side door. We both followed like well-trained cocker spaniels, wondering where we were going. As we got out on to the sidewalk, the other photographer noticed us. He came sprinting over, backpedaling in front of us, and started shooting. It felt weird having my picture taken by a paparazzo. Clint didn’t bat an eye. No matter what this guy did, Clint didn’t react. At one point the paparazzo knelt down on the sidewalk, right in Clint’s path. We all kept walking, and Clint stepped right over him as he bent over backward, still shooting.

After a while we reached our, or Clint’s, destination; Eastwood for Mayor campaign headquarters. This is where I wanted to be in the first place. There weren’t many people in there, and the few who were there didn’t pay much attention to the candidate. I sized up the light, overhead fluorescent lights and a few spotlights, not the greatest, but I’ve dealt with worse.

Clint continued walking through the front of the storefront and towards a back room. I couldn’t believe he walked through a perfectly good, photogenic campaign headquarters and into a small, probably dark, back room. I slowed down, hoping Clint would get the message. He didn’t even break stride; he was going to that back room.

I was trying to figure out if I could somehow force Clint Eastwood into staying in the adequately lit campaign headquarters. Clint opened the door to the dreaded back room. I started gesturing toward the main room, Clint looked at me, squinted his eyes and walked into the back room. You don’t GET Clint Eastwood to do anything, you don’t even get his attention when you try to.

I was now imagining a photo of Clint with a mop, a broom, and a ‘Employees must wash hands before returning to work’ sign behind him.

Why didn’t I try harder to get him to stay out in the main room? Was I actually believing a probably made up Hollywood tough guy persona? This is just a tall guy with squinty eyes, I should be able to get him to do what I want. I’ve gotten tougher people to do what I needed them to do. Besides, he’s probably a perfectly reasonable man. He’s a director, he’ll understand the need for proper lighting and a good background in a photo. I’ll appeal to his reason.

Clint was now inside the back room. I followed him in and once again opened my mouth to speak. As I did I notice a nice large window. Looking around I saw that it wasn’t a small, dark, broom closet, but a large, nicely lit meeting room with a clean background and plenty of room to work.

I must have psychically gotten through to him. He obviously succumbed to my shear force of will and went to where I needed him to be.

Okay, he knew where he was going all along, and he does know how to find the light that will make him look the best. I never should have doubted him.

I started shooting as he sat down in a folding chair and putting his feet up on a table. He was talking with the reporter, but looking out the window. The light on his face, and the direction he was looking made perfect use of his chiseled features. Who would have thought that Clint Eastwood was photogenic?